“Hold still we're going to do your portrait, so that you can begin looking like it right away.”

― Hélène Cixous, The Laugh of the Medusa

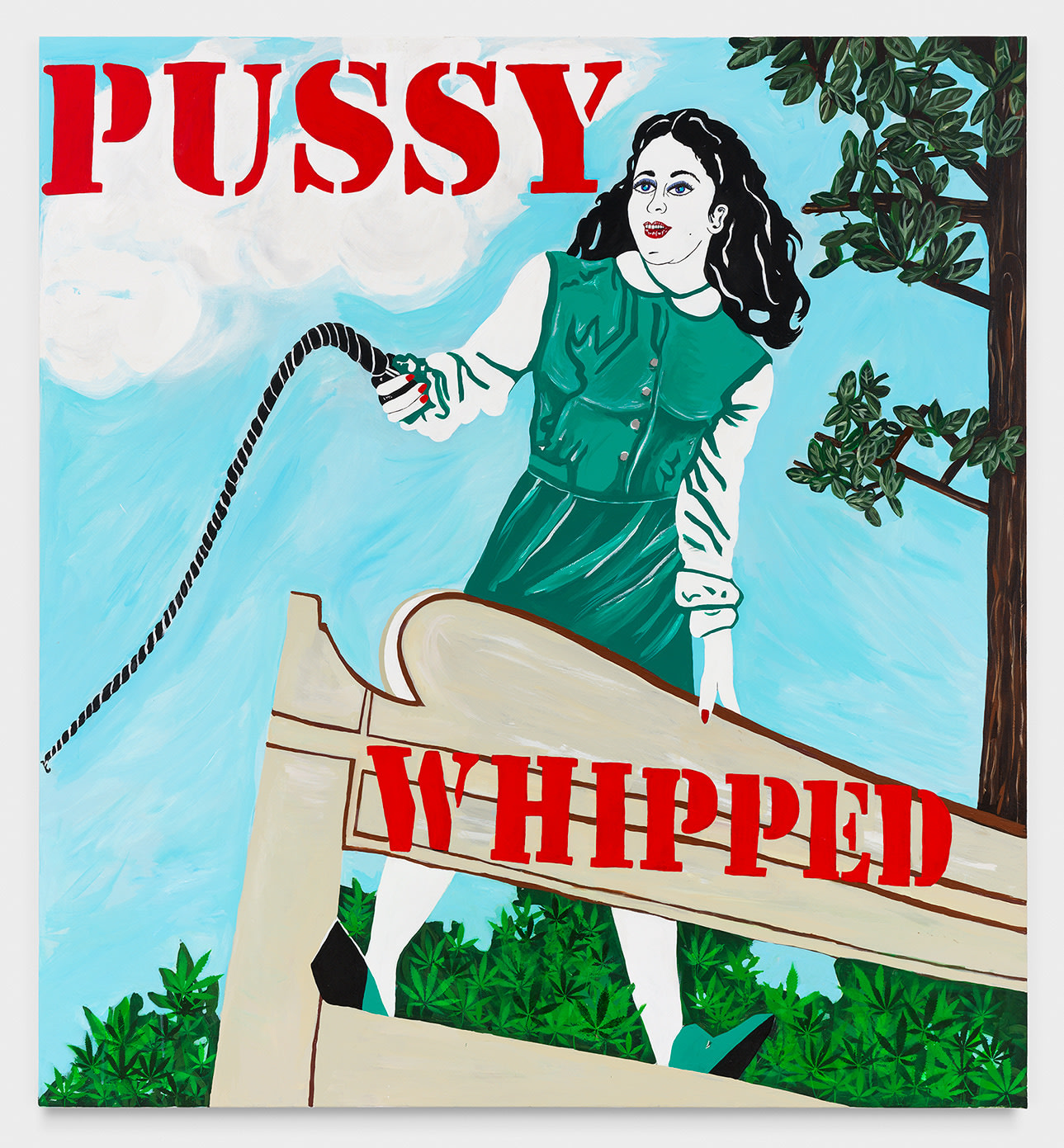

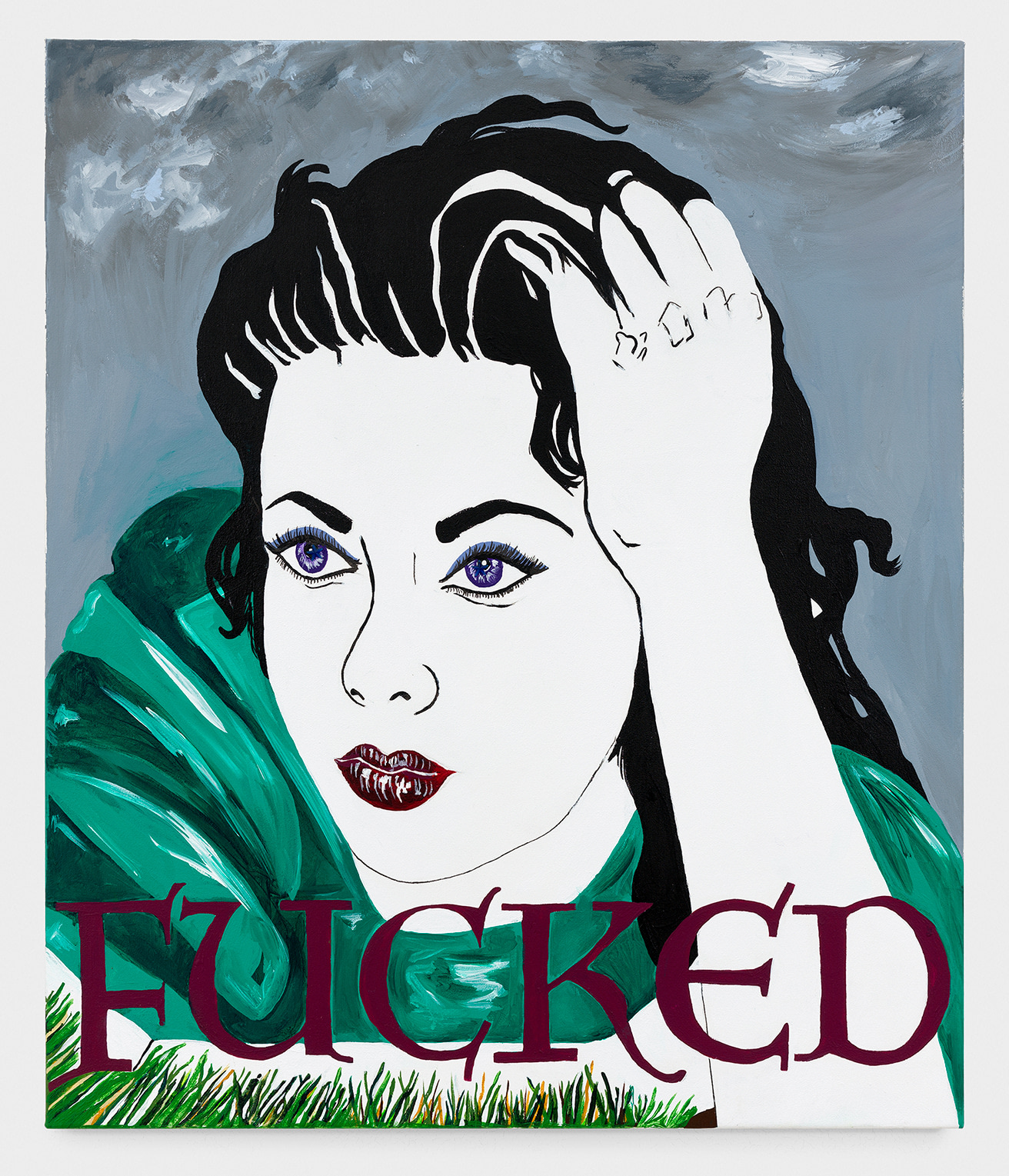

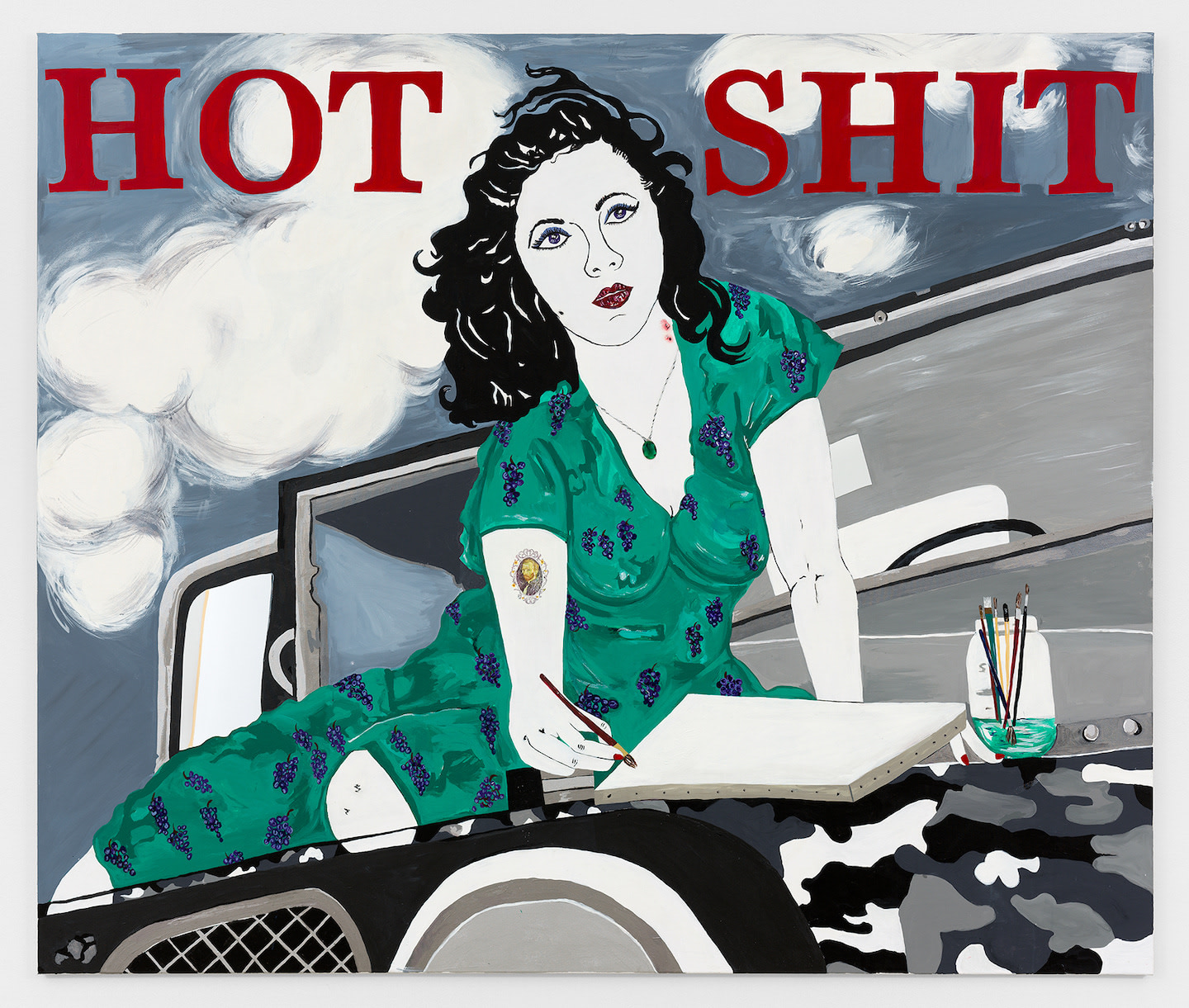

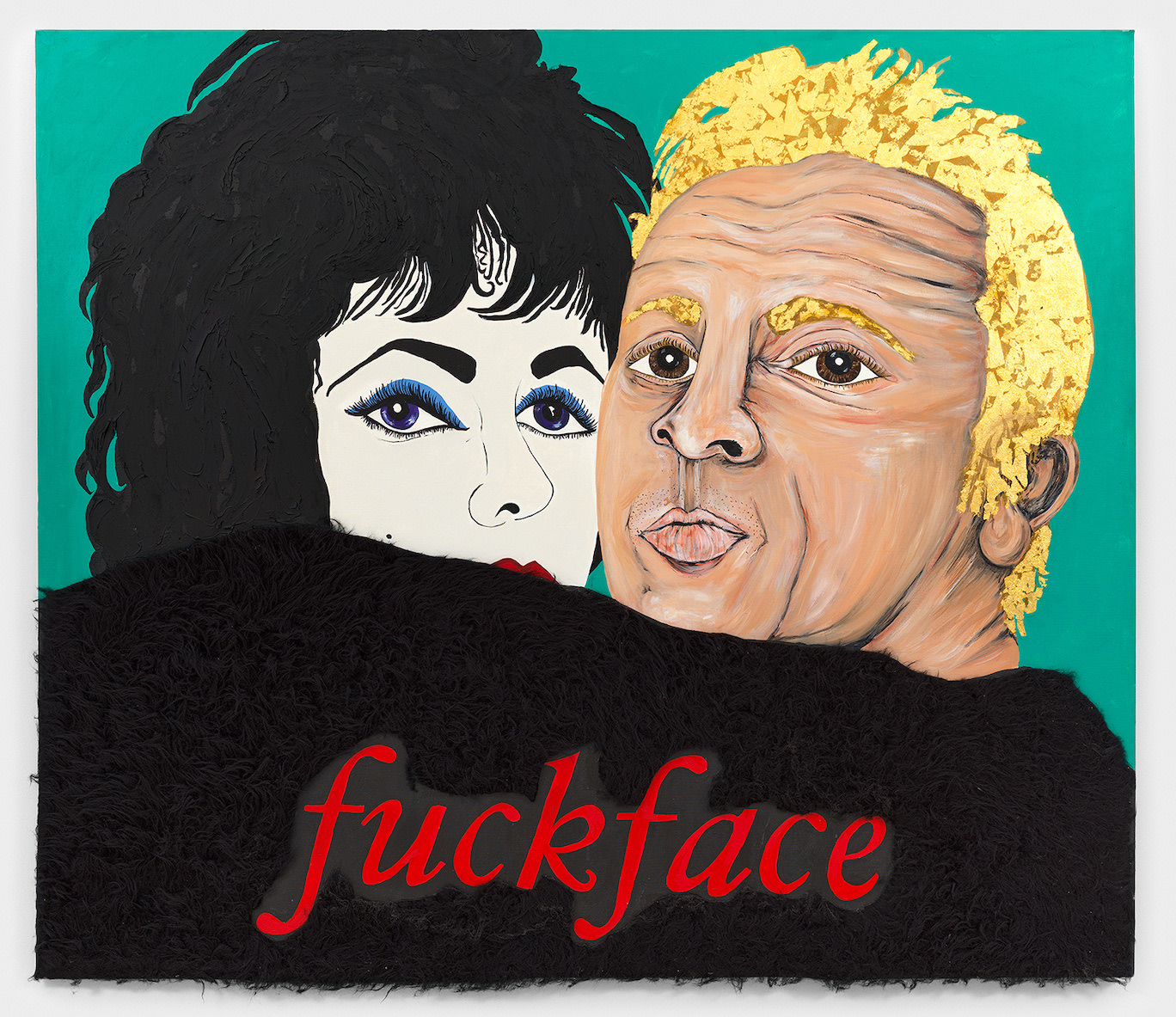

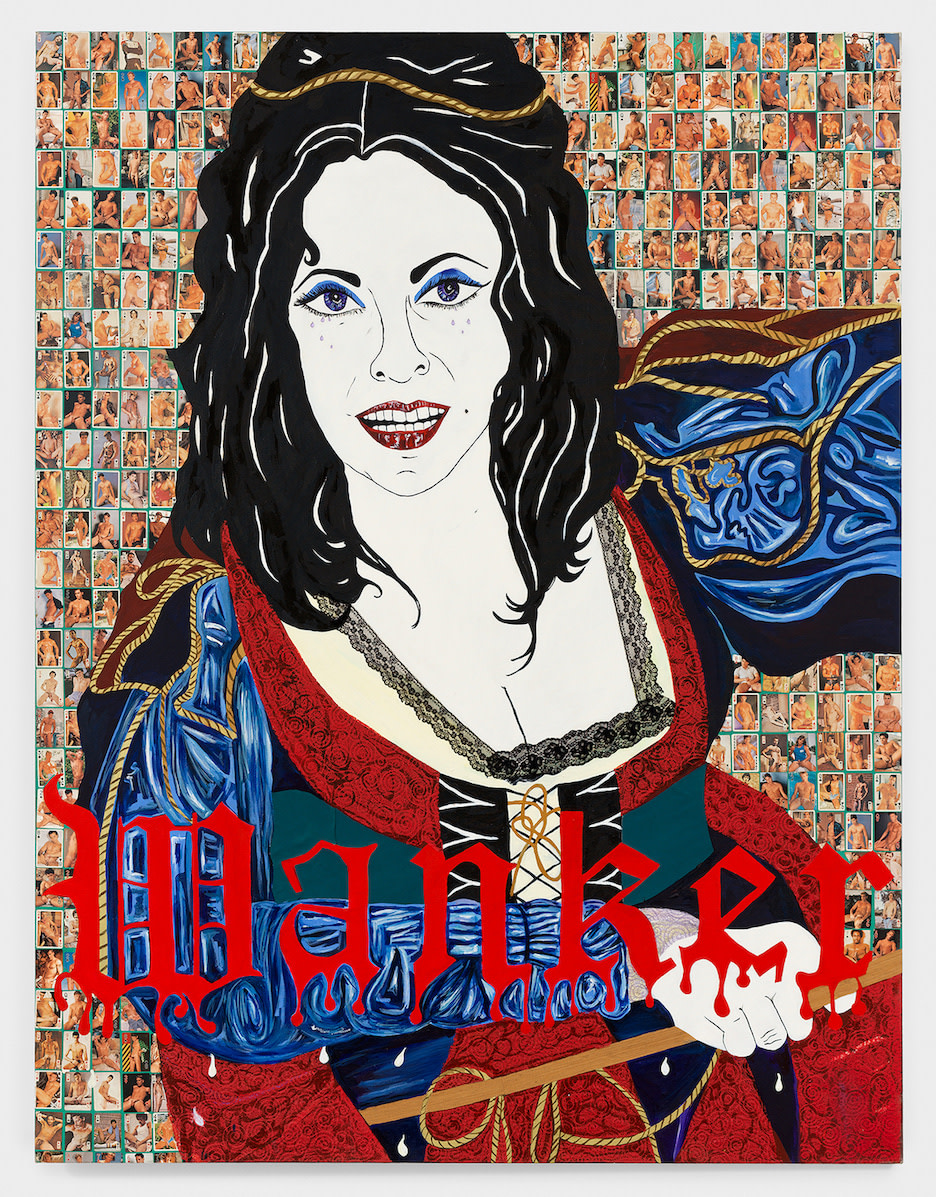

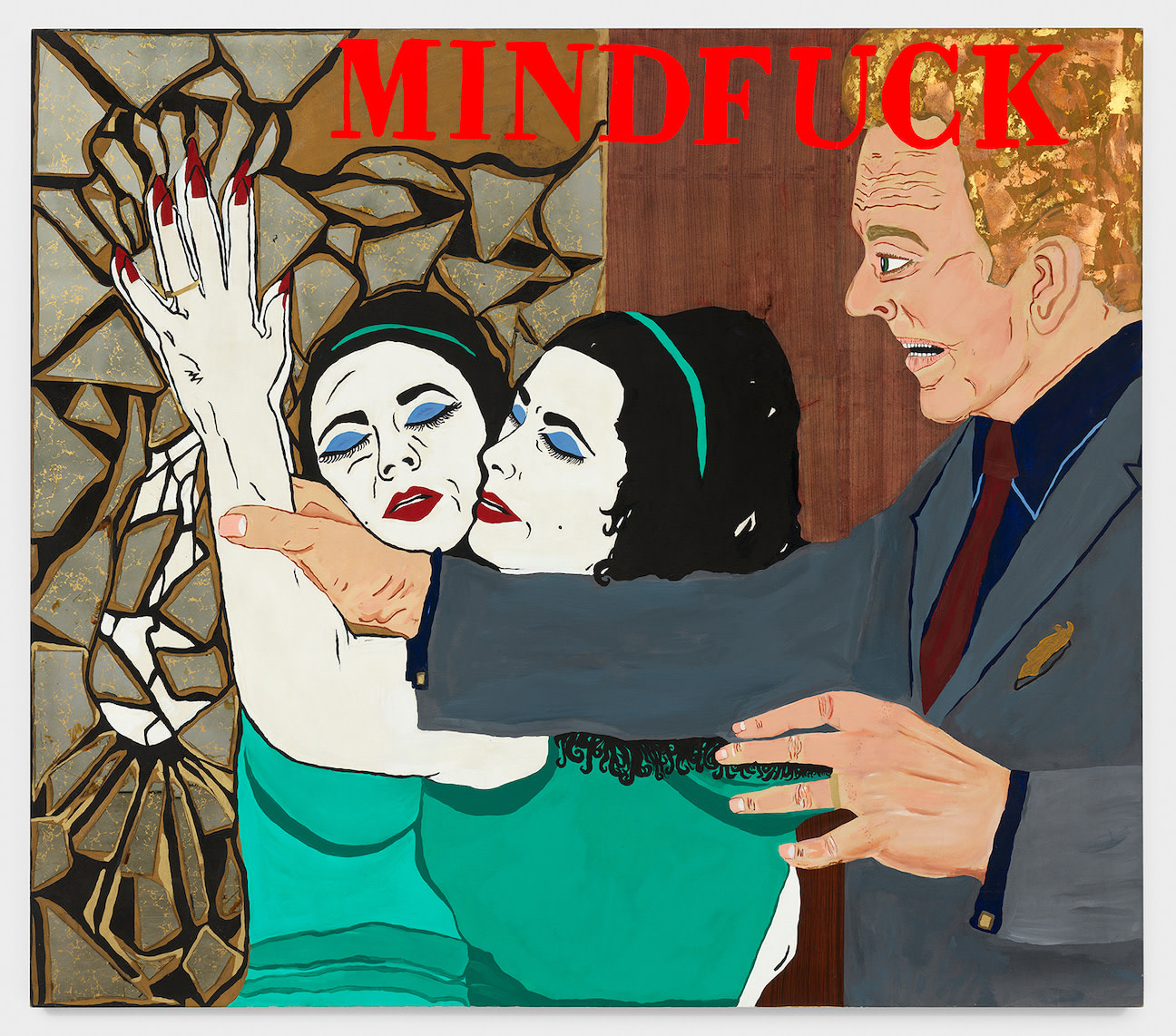

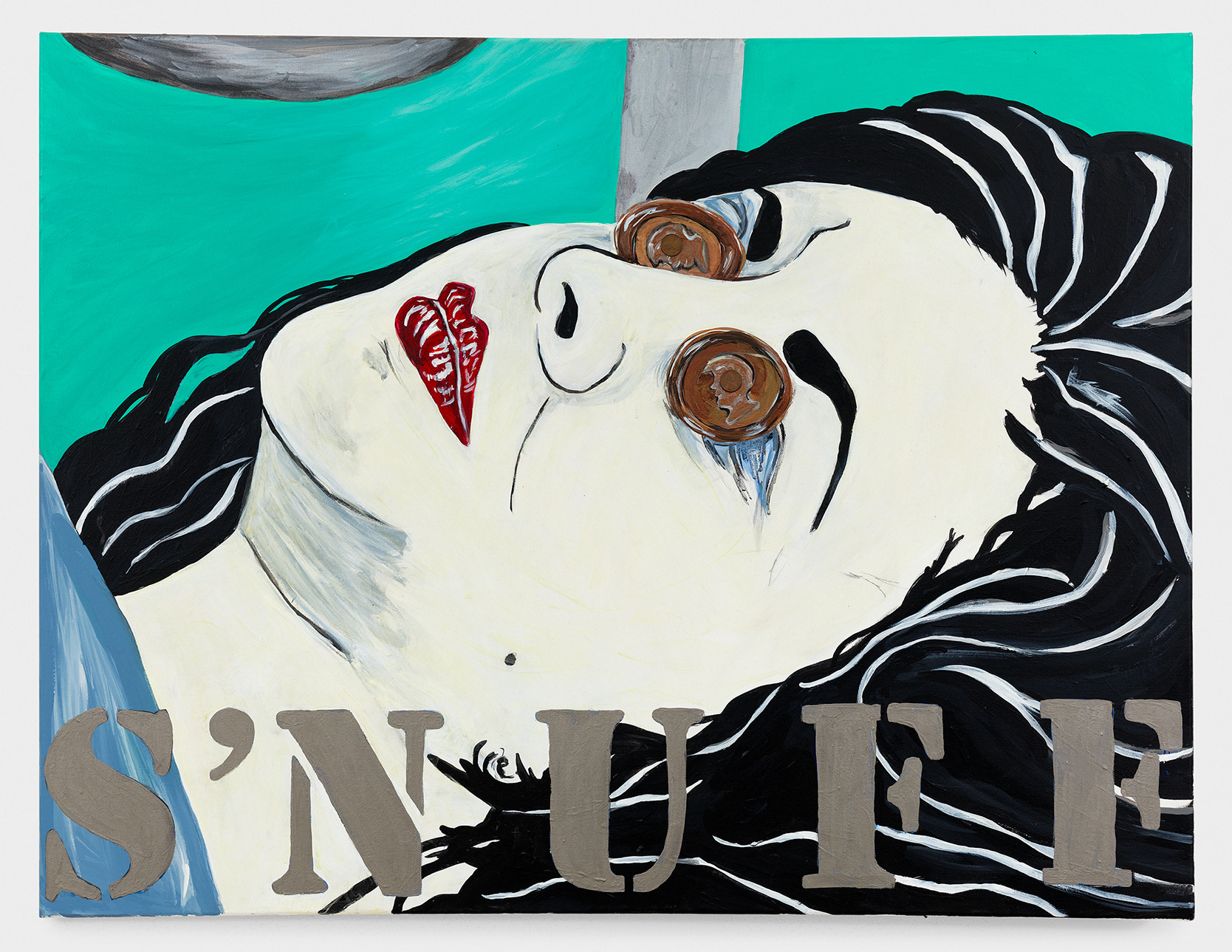

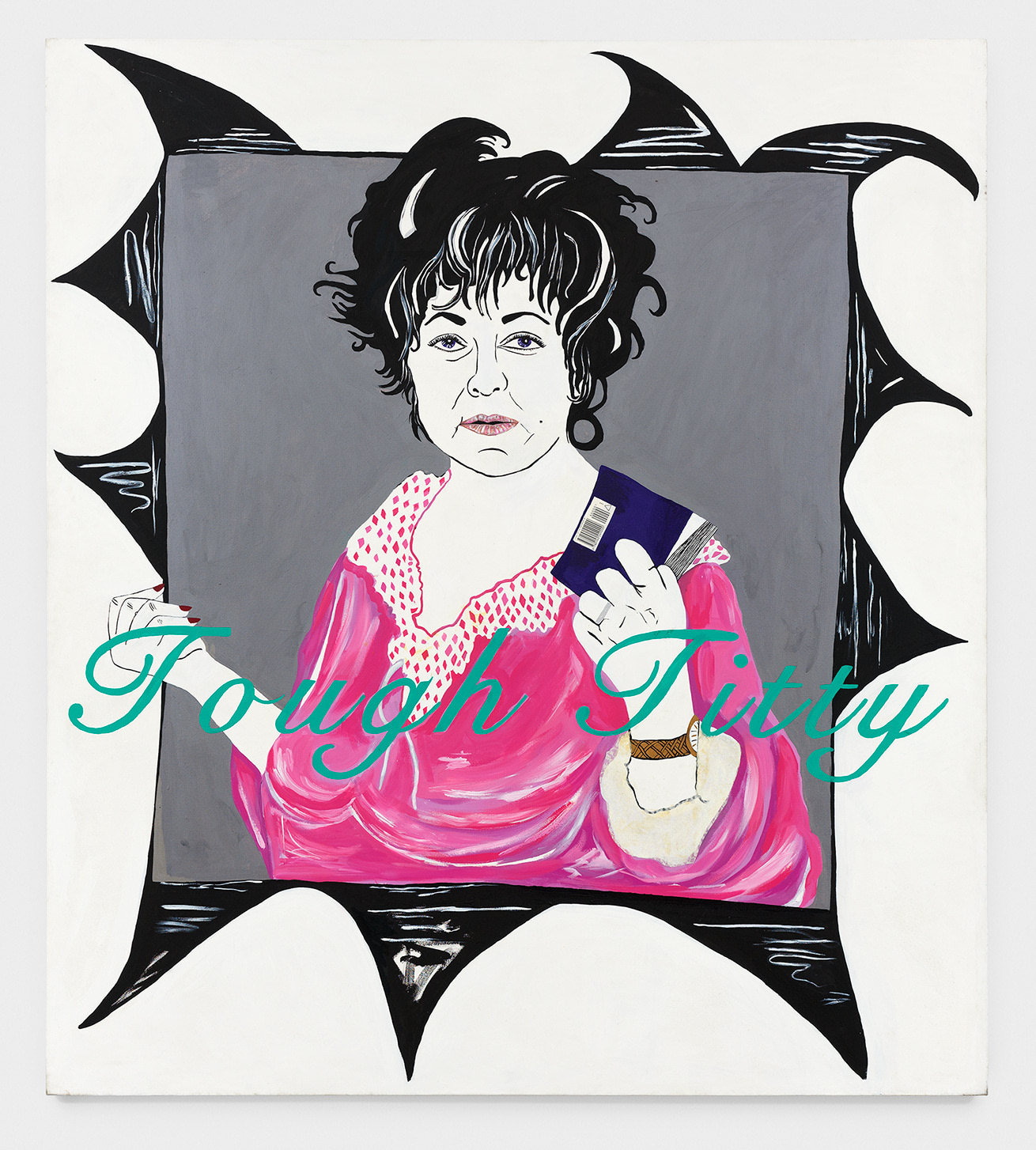

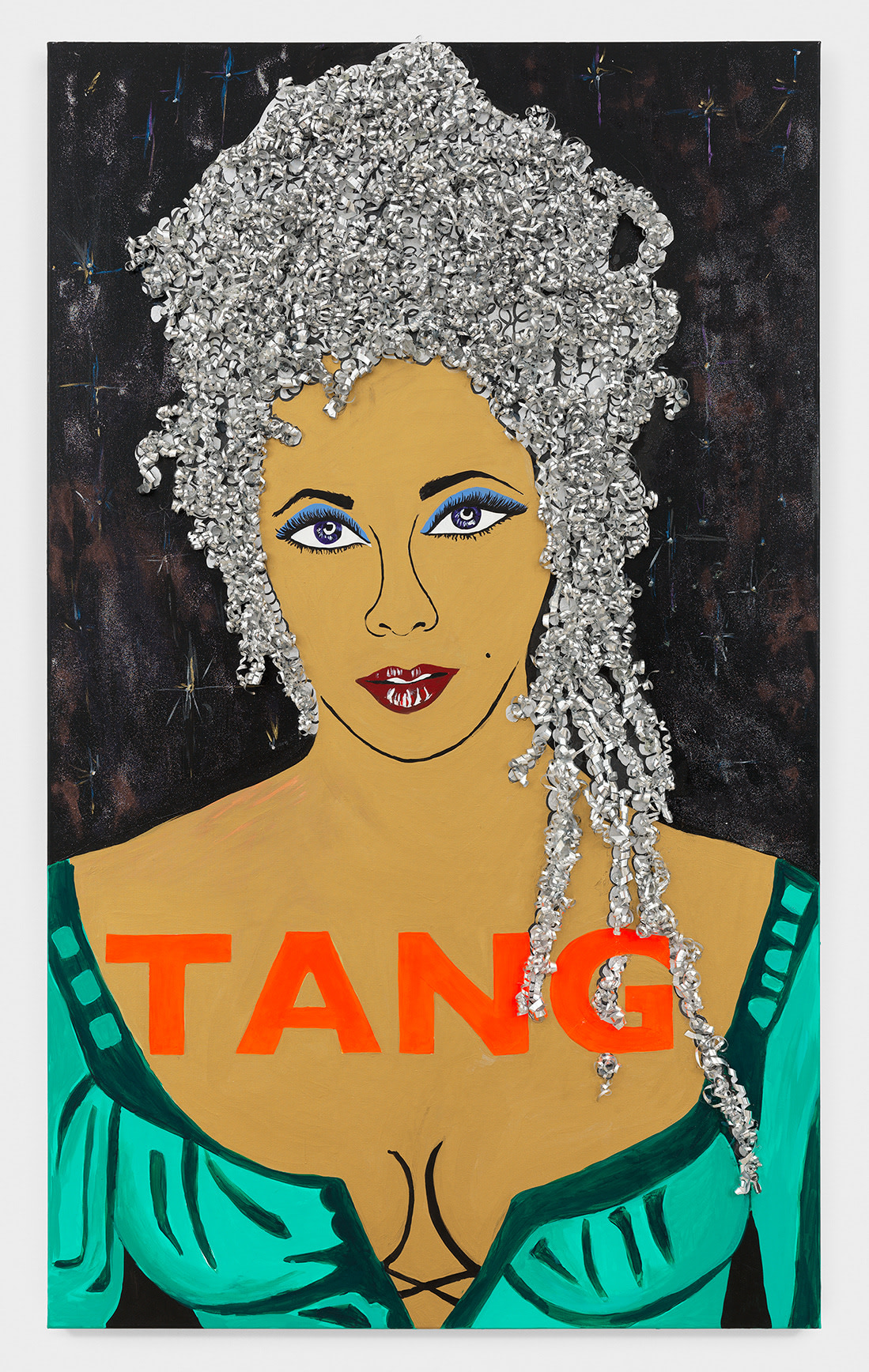

Since 1982, artist Kathe Burkhart’s ongoing conceptual project The Liz Taylor Series has mined a distinct terrain within the canon of feminist art merging provocative image and text to critique notions of gender, sexuality, power dynamics, and the body. Drawing on depictions of actress Elizabeth Taylor from film stills, publicity portraits, tabloid shots, and other visual sources, these works often incorporate unexpected collage elements—including fencing, straw, faux fur, and temporary tattoos among others—that simultaneously undermine the expectations of a painting while questioning the delimiting boundaries between the private and public, the personal and the political.

Throughout the series, Taylor is neither a mere avatar for the artist nor a subject of Warholian meditations on celebrity and reproduction; rather, Burkhart uses the star as a performative armature—a mobile inhabitation of lived experience elaborated within the slippage between projection and identification. As both a singular icon and a cluster of archetypes—ingenue, homewrecker, cougar, and crone, among others—Liz Taylor represents a chaotic zone of contact that exceeds the purview of a single persona. These discordant versions of a self, as dispersed across varied gestures and multiple media, allow Taylor to become a mutable signifier, a readymade embodiment capacious enough for Burkhart’s appropriation. Whether used in a distinctly autobiographical manner or as a general critique of the double-bind women endure under the patriarchy, Liz can be Liz, can be Kathe, can be anyone.

The use of text, most often in English and Dutch, amplifies Burkhart’s own voice, the slang phrases acting as both sly visual corollaries to the image represented, as well as frank truths implicating the viewer in a critical dialogue. For example, the work S'NUFF: from The Liz Taylor Series (Ash Wednesday), 2016, depicting a dead Taylor in phosphorescent paint with coins weighing down her eyes, employs the double meaning of the phrase to volley between humor and pathos: simultaneously exclaiming with exasperation that “it’s enough!” and alluding to the urban legend of the snuff film. Either read as a dark joke or a blunt statement on mortality, each interpretation alludes to an end condensed into the image of Taylor’s character. Yet Burkhart’s work grants the actress an afterlife that exceeds both the diegetic frame of her oeuvre and specific personal events. In a more recent work, Cut Me a Fucking Break: From The Liz Taylor Series (AP Press Photo), 2020, Burkhart reanimates a candid shot of Liz with aspects of autobiography, going so far as to append a face mask to the canvas, bringing the star into the Covid era.

Steeped in feminist theory, Burkhart’s The Liz Taylor Series avoids stable and obvious interpretations that conform to the limited number of constricting social archetypes offered to women via pop culture’s mass dissemination. Rather, of the re-presentation of Liz Taylor across a wide range of affective and auto/biographical iterations, the artist herself has stated, “an emotional identification of this kind provokes resistance, transgression, empowerment, and perhaps analysis of the mechanics of oppression in one’s personal life.”

Kathe Burkhart is an interdisciplinary artist and writer. She has been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions including Rozenstraat a rose is a rose is a rose, Netherlands; Kunsthalle Fri Art, Fribourg, Switzerland; MoMA PS1, New York; and Participant Inc., New York; among others. Burkhart participated in the 45th Venice Biennale (1993), and other group exhibitions including Fast Forward: Paintings for the 1980s at the Whitney Museum, New York; and NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star at the New Museum, New York. She has published four books of fiction, in addition to a vast collection of poetry and essays. Her work is in the collections of The Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; The Whitney Museum; The Art Institute of Chicago; and the SMAK Museum, Ghent.